This monk I met during a field trip my Introduction to Buddhism class took to a famous Buddhist temple in Beijing. After a tour of the temple grounds and a delicious vegetarian dinner, we all sat down inside of a prayer room that looked very similar to the prayer room that I sat in for so many Sundays of my childhood. We then had a Q&A session with one of the monks of the temple, with my professor acting as a translator. I timidly raised my hand to ask the first question of the night. I remember my voice shook as I tried to explain my family background and what had happened to me in Xia’he. I asked him what he thought of my story. I remember my friend, who sat next to me, pat my back in quiet support, hearing the emotion in my voice and knowing that the moment had meant something personal. The monk listened intently as I told my story, shifting his weight on the cushion he sat upon as my professor translated what I said into Chinese. Then, he gave me his explanation.

The Buddhist monk told me that what I had felt could have been a reaction of my soul to the circumstances of that moment. In the Buddhist tradition, the soul is reborn a number of times in a never-ending cycle. He proposed that I could have been a Buddhist in my past life, and my soul, in that moment, could have remembered that it was Buddhist in the past life. I was brought to tears because I unconsciously remembered that. He also said that if that particular explanation was a little far-fetched to me, I could have reacted the way that I did because what I had prayed for was very deep and personal, and because my prayers had come from the bottom of my heart, I was moved to tears as those prayers meant a lot to me.

After the field trip, the first thing I did was tell my parents about the monk’s words to me. My mom smiled with excitement on my phone screen as I told her and my father about the Q&A session. “Maybe it was meant to be for you to go to China and learn more about Buddha,” she said as a passing comment. But I took note of her words, and I held them in the back of my mind as I continued about my days in China.

Since I received that explanation, my heart felt a little lighter. My mom was certainly right that China was becoming a classroom for me to learn about Buddhism in a surprisingly subtle way. I felt like I could look at Buddhism in the eye, sit down, and have a proper dialogue with it instead of ignoring it like I had done for all of those years. I could see it in action in the lives of the people here. I knew, I knew, that deep down it held a very dear place in my heart. It was undoubtedly part of my cultural heritage, after all. I believed in many of its morals, and I had extensive knowledge about the religion. Yet I still had this weird complicated relationship with it, unable to call it my own because I still questioned it. Now that I had gotten to this point with it where I could comfortably reflect, I felt that I could search for an answer to the question I had been asking Buddhism for quite some time: “What role do you play in my life?”

One of the things that puzzled me about the religion was that it seemed contradictory as a result of its material culture. Buddhism is a religion that attacks the material world with such a vigor no other religion can compare. Yet material culture still exists within it. I didn’t understand why it is necessary for us to pray with prayer beads, to burn incense, and to read sutras as we chant. It disturbed me to see so many tourist sites along the Silk Road sell prayer beads and other Buddhist ritual items as souvenirs. So, what did I do to try and understand this phenomenon?

I wrote an extensive 13-page research paper about material culture within Buddhism for a class.

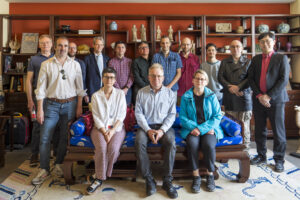

While researching information for that paper, my Buddhism class took another field trip to another different Buddhist temple, sitting down in a monk’s living quarters and having a very casual talk with him. The monk was named Yuan Liu. He spoke extremely good English and was very hospitable, constantly offering us more tea and more snacks to eat. As we enjoyed each other’s company, we were allowed to ask him any questions that we had about Buddhism. Obviously, I had to ask him about the role of material culture within Buddhism, both for my paper and for my own sake.

The answer that he gave me became an answer that I had been looking for.

He said that the items, like prayer beads, are a way to guide the mind, which by its nature is uncontrollable and easily distracted. Whenever anyone starts practicing the Buddhist belief, their minds start out as wild and uncontrollable. The rituals, the chanting, everything, serves as a reminder to practitioners of their belief and the path that they walk on. Perhaps most importantly, he reminded me that what really matters in Buddhism is the tempering of the mind and the discovery of inner peace and happiness through a simple life.

Again, the first person I called to tell this experience was my mom. She basically reiterated what the monk had told me. Perhaps the most significant thing she told me was that wearing prayer beads meant that one was always praying to Buddha, reflecting the dedication to the Buddhist way, even if one didn’t go to temple every Sunday or prayed all the time.

I contemplated on Yuan Liu’s and my mom’s words long after I turned in that essay. I slowly came to understand that all that stupid questioning I did was a result of me blatantly veering off of the path that my parents put me on during my times of turmoil. They had put me on that path because they believe that the teachings of the Buddha would allow for me to grow up into a responsible, strong, polite woman. They believe that the teachings could help me redirect myself when in times of difficulty. I’ve come to better understand that Buddhism isn’t a religion in which I have to do all these rituals to call myself a true Buddhist, but it is a guidance. Buddhism, at its core, is the nurturing of the heart and the spirit, and by passing down its traditions to me, my parents were nurturing my heart and my spirit, long before I’ve realized it. It’s taken me a trip to China to finally, truly, understand that. And that’s a powerful realization that brings me to tears.