Any surprises or challenges after coming here?

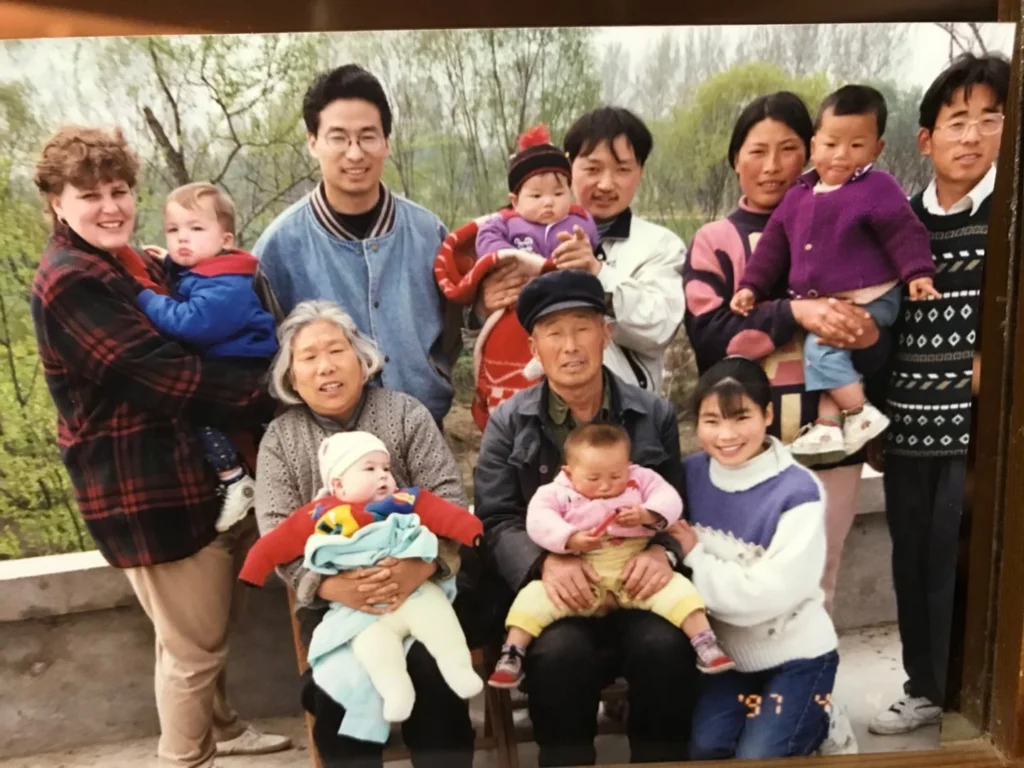

I think one of the things I wasn’t expecting was for the skills I learned in Italy – traveling alone, independence, fake it until you make it, learning the city well – to translate well here. I think I just had it in my head from all my previous China experiences that ‘everything would work out’ without really thinking: well, that’s because your dad was there, who is a native speaker. But whether I’m just wandering around Beijing with some friends or taking the train for a solo weekend away, I know whatever I’m doing, I can do it. Some of the biggest surprises I’ve had is when Chinese people recognize me as Chinese. One of the things my Chinese professor has told me is that she thinks that people with Chinese mothers tend to look more Chinese, while people with Chinese fathers look more white (assuming their mothers are white, of course). I think I agree. It’s a rare day in the States when somebody sees me and doesn’t think I’m just another white person. I’ve had to prove my ethnicity by showing my driver’s license with my surname, for example. That hurts. But here in China, despite getting some looks for being obviously a foreigner, people see that I have Chinese heritage. I’ve even had people that are part of a company that teaches Chinese people English ask me if I would like to learn English with them. That’s been pretty nice. But on the flip side, my Chinese language skills aren’t everything I want them to be. I can’t communicate directly with my grandmother because even though I’ve learned so much since 2013, she speaks only in our regional dialect that is too thick of an accent for me to understand, so my grandfather sort of translates for the both of us, but even then I never really catch all of what he says. Like I said, I can’t really read, and there’s so much I can’t say.

Any tips or advice to share with others with Asian heritage?

Since I was raised in Minnesota, in a predominately white area, I didn’t have any non-white friends growing up, with the exception of one South Asian girl who went to a different high school. There were ten or less East Asian kids in my graduating class, and about that same number of Southeast Asian kids. There were a few more than ten African-American kids, and little to no Latin kids or Native Americans. So when I went to college in the great diverse city of Chicago, one of the first things I stumbled into was an Asian-interest (not Asian-exclusive) sorority, built for and by the Asian community. It was amazing to go from no community at all to this wonderful, multi-talented, and welcoming organization of girls from backgrounds from all over the world, not just East Asia, and I bring this up because three of my sorority sisters came to China and The Beijing Center before me. But all of them were adopted Chinese women. They offered me advice on where to eat, what to do, what to see, but none of them could really relate their cultural experience with the journey I was going on. They had their own, different but no less important, relationships with China and their heritage. So my tip to others with a connection to China like mine, I strongly suggest doing it and coming to Beijing. I can’t speak to everyone’s experience – goodness knows that everyone comes from different backgrounds, not adding cultural connections into the criteria, but even with hesitation, come see your China. I’m staying here until mid-August because this is my only chance at the undergraduate experience to be here. I’ll tell you to study the language, yes, but that goes for everyone, Chinese at all or not. For me, maybe staying the longest will make it the hardest to leave and hurt the most once my plane touches ground in Minnesota again. But I’m okay with that. My Chinese heritage is a big part of who I am, the same as my American. But my life and experiences aren’t as easy to split half and half like my genes, so I have to do what I can now. Life isn’t like in the books and movies, where somebody suddenly discovers this hidden part of themselves but everything is okay, easy to learn, and useful. You have to work to know and use this thing that makes you unique and strong.

So that’s sort of my advice, to anybody with Chinese heritage, no matter the type or the amount or even your level or history of connection with it. If you want to know the world, and know yourself, come to China. The Asian-American culture, and the American one too, is so different.

And go eat at Hangzhou Xiao Chi when you come here, if it’s still around outside of East Gate. I recommend the Qiezi Gai Fan, even though it’s not exactly on the menu (yet.)

Sabrina Lin

My name is Sabrina, and I came to TBC as a junior from Loyola University Chicago majoring in Statistics, minoring in Information Systems. Born and raised in San Francisco, CA, I grew up in a predominately Chinese American community where within the public school system, we got Chinese New Year’s off. Both my parents immigrated to the United States from China; I grew up in a culturally Chinese household, speaking Chinese and eating delicious Chinese food daily, in addition to observing most of the major Chinese holidays growing up.