3. Exploring China

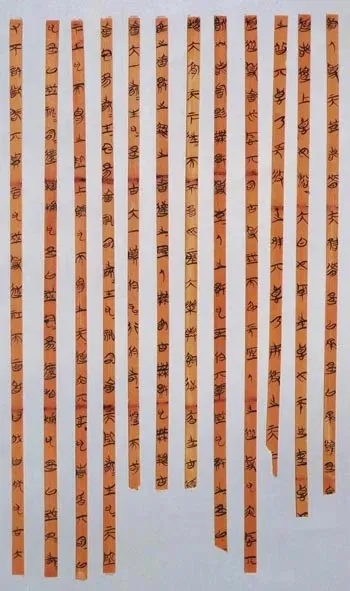

Before I came to teach at TBC, I had visited China many times during the summer to attend conferences or to teach during the summer sessions. I made some good friends in China as a result, and Beijing Normal University warmly extended an offer to me, which was a precious opportunity, so I accepted. The year was 2016. Since arriving here, I have been teaching Chinese philosophy, with a general focus around Daoist thoughts. I have offered two courses at Beijing Normal University, both for Chinese students or international students from other countries. Then, I was introduced to the TBC staff by my close friend Robin Wang, a professor of philosophy at Loyola Marymount University. I was interested in TBC and wanted to join. After TBC restarted the course program and recruited students again, I officially became one of the TBC members to teach Daoism-related courses this semester.

In fact, my relationship with China began long before I came to work here. I studied Chinese in Taiwan for a year, and I came to Mainland China for the first time in 2002, and from 2005 onwards, I would come to China in the summer to attend conferences or teach summer courses, and these annual visits continued until the year I moved to China to work officially. I studied Chinese for a long time, and for some other foreign scholars, the language is a barrier. If one doesn’t know Chinese at all, their academic research and daily work become difficult.

I like where I am now, but if I could do it all over again, I wish I had more time for myself in my busy work schedule to travel around the country again. I once went to a Confucian ceremony in Qufu, where the park behind the temple had a large circle for people to walk around, and where it was said that Confucius’ descendants would worship their ancestors.

Rather than visiting museums during trips, I prefer climbing mountains more. The process of climbing is a great opportunity to get in touch with nature, and I also enjoy the time I spend climbing with my friends. I now have a friend who is very passionate about climbing as I am, and we meet up every time.

Of all the mountains I’ve climbed, my favorite is Emei Mountain, but one of the best climbing experiences was at Jizhu Mountain in Yunnan. It was a climb many years ago, around 2005, when I didn’t even have a cell phone — or rather, my cell phone didn’t work properly in China. As I was about to start the climb, I met a group of “pilgrims”, four older women and the daughter of one of them. They were older than me, but they were very skillful in climbing, which shocked me at the time.

When we reached the top of the mountain, close to the clouds were monasteries inhabited by Buddhist monks, and when the clouds cleared, the village was at the foot of the mountain, and there was another monastery visible. The higher monastery was inhabited by monks and the lower one by nuns, a marvelous combination of yin and yang between the mountain and the clouds. The scene was so interesting that I took photos, and one of them later became the cover of my first book.