The Rita Liu

Cartographical Collection

(1584-1837)

Selected from

the Anton Library for Chinese Studies

The Rita Liu Cartographical Collection

About the Collection

The Rita Liu Cartographical Collection exemplifies the curiosity inherent in all individuals. Over hundreds of years, people from diverse backgrounds embarked on journeys to China, seeking and transmitting knowledge about places previously unseen by those who shared their culture, beliefs, and ideas. Beyond their travels, these individuals crafted maps, offering novel—and often groundbreaking—perspectives of the world. Instead of hoarding their newfound knowledge, these adventurers chose to engage and share the enchantment they experienced. We hope that all readers of this booklet are inspired to do the same.

Catalogue

-

Chinae, Olim Sinarum Regionis (1584) 01

-

Martino Martini and Joan Blaeu Maps 02

-

La Chine Royaume 03

-

Jean Baptiste d’Anville and Jean Baptiste Du Halde Maps 04

-

New and Accurate Map of China Drawn from Surveys Made by Jesuit Missionaries, by Order of the Emperor (1747) 05

-

Empire des Mongols, Conrad Malte (1837) 06

-

A Sketch of journey from She-Hol in Tartary by Land to Pekin and from Thence by Water to Hang-Tchoo-Foo in China 07

The Rita Liu Cartographical Collection

Collection introduction

01

Chinae, Olim Sinarum Regionis (1584)

This map boasts an impressive array of ‘firsts’: it marks the inaugural instance of a printed European map specifically dedicated to China, the first depiction of China in an organized atlas, the earliest portrayal of the Great Wall of China, the pioneering representation of wind wagons, the first map to name the Philippine Archipelago, and the earliest Western printed display of Chinese characters on the verso. Notable and distinctive features include its Western orientation, ornate decorations, vibrant colors, and references to historical and apocryphal points of interest for the 16th-century atlas reader.

Luiz Jorge de Barbuda, SJ (1564? -1613?) remains a mysterious figure in Portuguese cartography, with much about him shrouded in uncertainty. In 1582, he received a commission from Philip II of Spain to create navigation charts and world maps. The inclusion of his map in Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum was accompanied by a detailed description of China and the Chinese language, drawn from Bernardino de Escalante’s Discurso de la navegacion que los Portugueses hacen a los Reinos y Provincias de Oriente (1577), the first book published in Spain about China.

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598), a Dutch cartographer, is credited as the pioneer of the modern atlas and the founder of the Netherlandish school of cartography. The initial edition of the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum was printed in 1570, featuring 53 maps, a number that swiftly expanded with subsequent editions. In 1575, Ortelius was appointed the Royal Cartographer to Philip II of Spain, and his works remained the authoritative standard for over 75 years.

02

Martino Martini and Joan Blaeu Maps

Who They Were

Martino Martini, SJ (1614-1661), a Jesuit missionary hailing from Trento (now Italy), played a crucial role in advancing the Jesuit mission in Hangzhou, China. Serving as the Jesuit Superior in Hangzhou, he gained substantial access to surveys and valuable information, which he later brought back to Europe.

Joan Blaeu (1596-1673), the son of the cartographer Willem Janszoon Blaeu, assumed control of the family business following his father’s passing. He held the position of hydrographer for the Dutch East India Trading Company and gained renown for the meticulous detail, exceptional quality, and aesthetic beauty of his maps.

Imperii Sinarum Nova Descriptio (1655)

The Imperii Sinarum Nova Descriptio stands out as the most precise and authoritative map of China in 17th-century Europe, compiled by Joan Blaeu and Martino Martini, SJ. This map holds the distinction of being the inaugural Western atlas specifically dedicated to China, Korea, and Japan. Building upon the knowledge accumulated after the publication of Luis Jorge de Barbuda, SJ, and Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum in 1584, it provides a more accurate depiction of distant landmasses, such as recognizing the peninsular status of Korea and delineating the islands of Japan. Notably, it also marks the first Western map to illustrate the curvature of China’s coast, challenging previous cartography that depicted it as a relatively straight line.

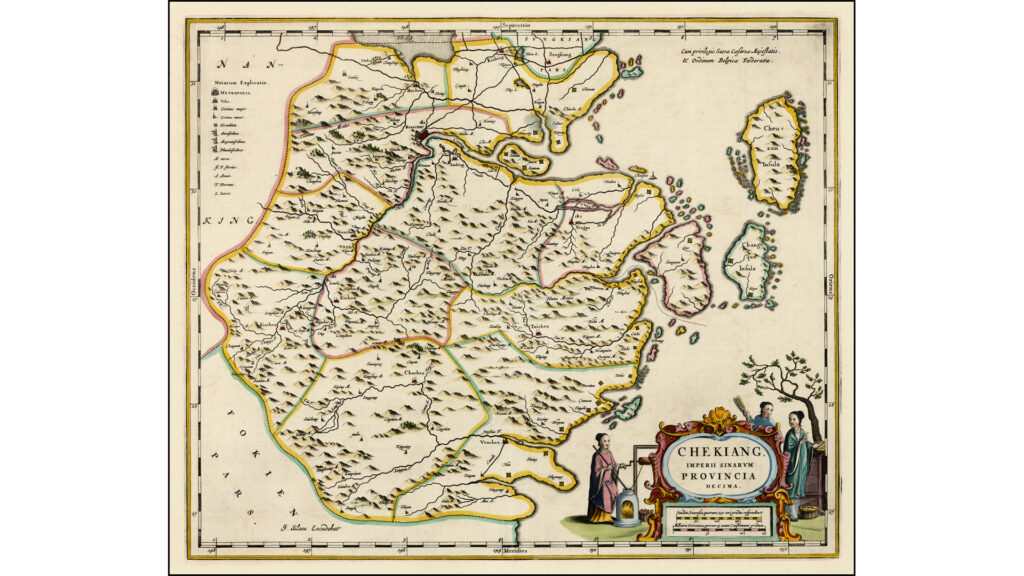

Chekiang Provincia, Imperii Sinarum (1655)

The Nova Descriptio provides a comprehensive overview of China and its adjacent regions. Other maps within the Imperii Sinarum series in the Novus Atlas Sinensis focus on specific provinces, such as Chekiang (Zhejiang) and Iunnan (Yunnan). The Chekiang Provincia map depicts various day-to-day activities, including harvesting and games, while mines are marked with small flags indicating their contents. Notably, the cartouche features an illustration of a man engaging in the process of ‘silk reeling,’ believed to be the earliest European depiction of silk production in China.

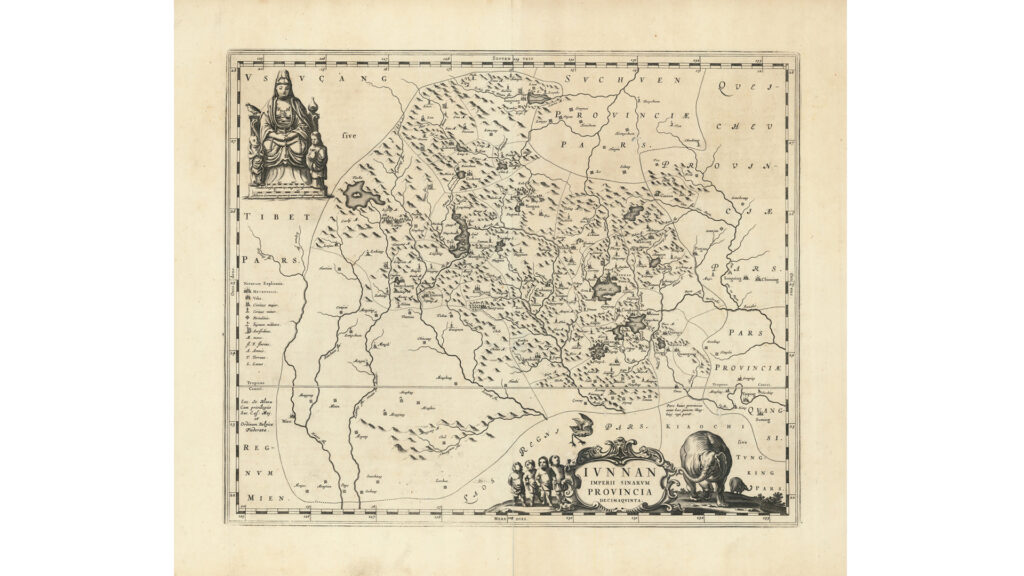

Yunnan Provincia, Imperii Sinarum (1655)

Martino Martini, SJ, and Joan Blaeu’s map of Yunnan Province is the first printed European map of the Yunnan region, encompassing the territory between Tibet and Guangxi Province, Sichuan Province and Laos, Burma, and Vietnam. The map is adorned with depictions of indigenous flora and fauna, including tropical birds and elephants, along with the inclusion of four children positioned near the cartouche.

03

La Chine Royaume

This map, published in 1658, is believed to be derived from a Chinese map that Matteo Ricci, SJ, copied in 1590 and subsequently brought to Rome by Michele Ruggieri, SJ. The original Chinese map is Luo Hongxian’s four-volume Ming Atlas, Guang Yu Tu (1579). Notably, the Korean peninsula is depicted as a peninsula, albeit with a distinctive curvature, which was unconventional for the period. Additionally, the northern tip of the Philippines is included. In the lower right-hand corner, Sanson’s explanation is adorned with Pheme, the personification deity of fame and renown. It also makes references to the prior work of Michael Boym, SJ, and Martino Martini, SJ.

Nicholas Sanson (1600-1667) was a French cartographer, often considered to be the father of French cartography for his influence and output. These maps were researched and often accompanied by explanatory notes on the recto. Sanson’s contributions marked a pivotal shift of cartographic excellence from the Netherlands to France. He held the esteemed position of Official Royal Cartographer and served as a tutor to Louis XIII.

The note in the corner reads “In 1590 while in Rome Matheo Neroni drew a magnificent, most unusual, and very large map according to Fr. Michele Ruggieri’s explanations of drawings found in four books printed in China. It is currently kept in the study of His Royal Highness Monseigneur the Duke of Orleans. My map is only an abridged version of Neroni’s work. Because of a lack of space, I was able to include only cities of the first and second ranks. While engraving it, I looked at Fr. Martino Martini La Chine and glanced at Fr. Boym’s still unfinished work, which he claims will be the best of all maps. Martini’s opus contains sixteen maps, one for each province, but they sometimes are less detailed than the one drawn by Neroni. When I attempted to reconcile all these maps I was confronted with great differences in names and numbers of prefectures (fu) and townships (si), not to mention the smaller places. All this leads me to believe that these maps are based on indigenous drawings by different Chinese authors and that it will be difficult to say who among them is the best…”

04

Jean Baptiste d’Anville and Jean Baptiste Du Halde Maps

Who They Were

Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville (1697 –1782) was a distinguished French cartographer who assumed the role of King’s Geographer in 1718. Renowned for his exceptional precision, he crafted more than 200 maps, earning a reputation as the preeminent cartographer of his era. His innovative approach transformed the field of cartography, as he deliberately left unknown areas blank and provided comments on uncertain information, eschewing the common practice of embellishing spaces with decorations or conjectural details.

Baptiste Du Halde, SJ (1764-1743), a French Jesuit priest, earned recognition as an authority on China despite never having visited the country. His work, Description de l’empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie Chinoise, stood as the most comprehensive compilation and analysis of sources on China during its time. This seminal piece sparked considerable interest in China across Europe, leading to its translation into numerous languages and the publication of multiple editions.

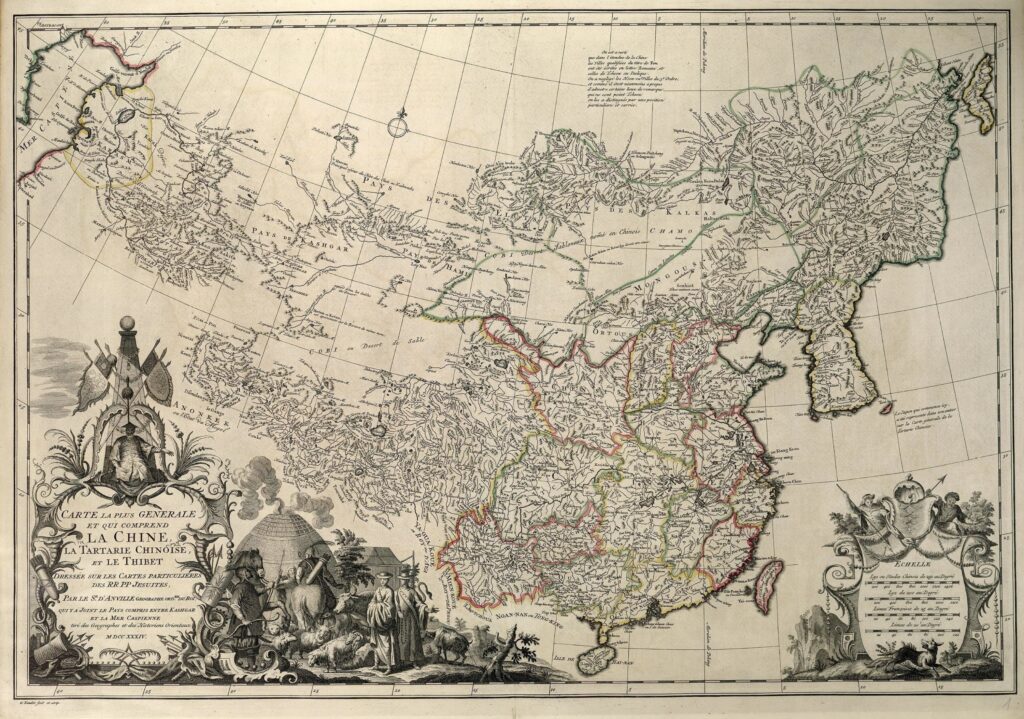

La Chine, LA Tartarie Chinoise et le Thibet (1737)

D’Anville’s 1737 map of China, Manchuria, and Tibet is widely recognized as the most exquisite printed map of the region from the 18th century. The depicted territory spans from the Caspian Sea to Sakhalin, the largest Russian island. The map intricately illustrates boundaries and landmarks, encompassing deserts, mountains, steppes, and the Great Wall with beautiful detail. It marks the second major European-published atlas of China, succeeding Martini and Blaeu’s Novus Atlas Sinensis. The maps featured in Description de l’empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie Chinoise originated from a collection crafted by Jesuit surveyors between 1708 and 1716, commissioned by the Kangxi Emperor and known as the Kangxi Atlas.

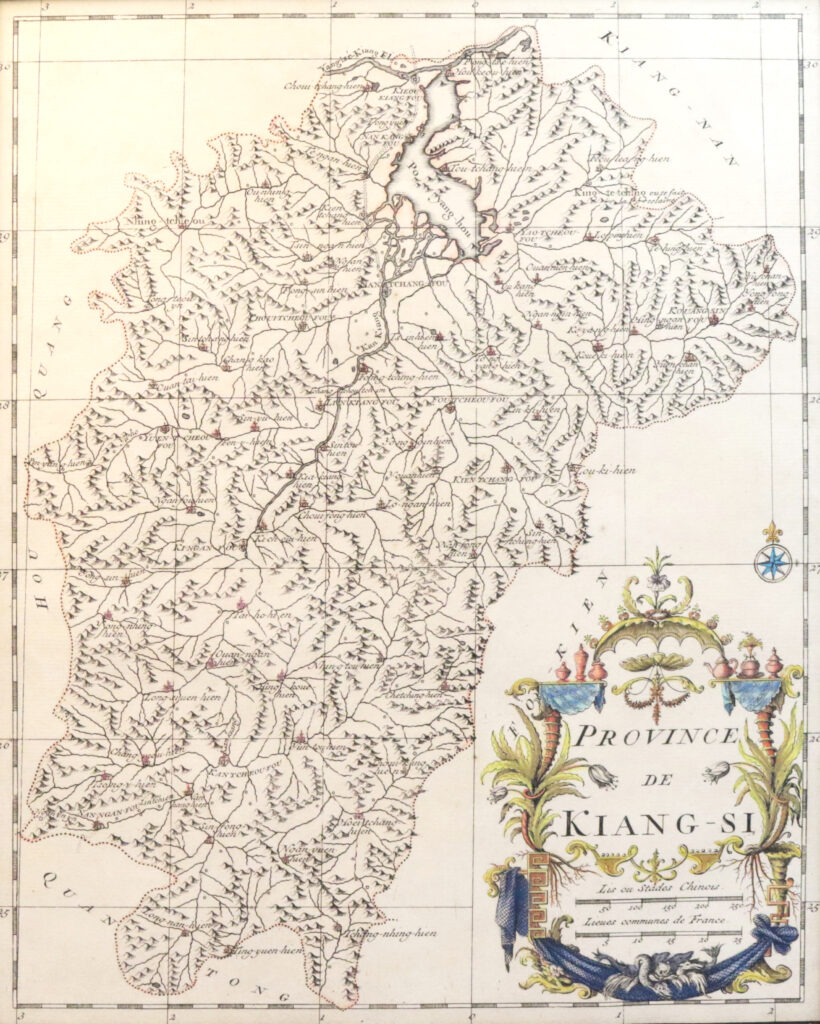

Province de Kiang-Si (1734)

05

New and Accurate Map of China

Drawn from Surveys Made

by Jesuit Missionaries, by Order

of the Emperor (1747)

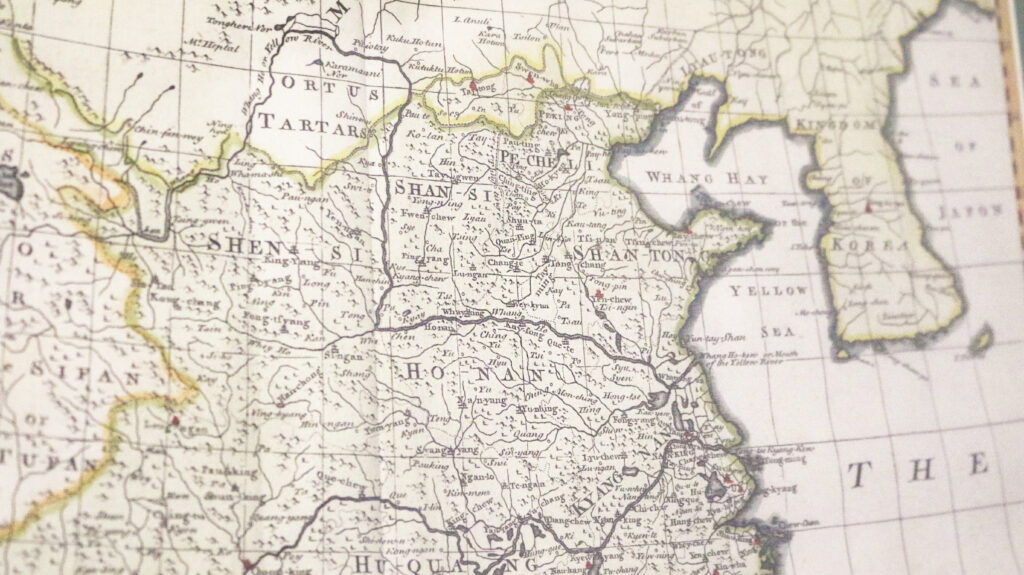

Emanuel Bowen’s 1747 map of China is heavily influenced by Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville’s original work, adapted and translated specifically for a British audience.

Emanuel Bowen (1694?-1767) was a distinguished British engraver and mapmaker renowned for his exceptional atlases and county maps. Throughout his career, he held the esteemed position of mapmaker to both George II of England and Louis XV of France. Despite his significant contributions, including training notable mapmakers like Thomas Kitchin and Thomas Jeffreys, Bowen tragically passed away in poverty.

The note in the corner reads “In 1590 while in Rome Matheo Neroni drew a magnificent, most unusual, and very large map according to Fr. Michele Ruggieri’s explanations of drawings found in four books printed in China. It is currently kept in the study of His Royal Highness Monseigneur the Duke of Orleans. My map is only an abridged version of Neroni’s work. Because of a lack of space, I was able to include only cities of the first and second ranks. While engraving it, I looked at Fr. Martino Martini La Chine and glanced at Fr. Boym’s still unfinished work, which he claims will be the best of all maps. Martini’s opus contains sixteen maps, one for each province, but they sometimes are less detailed than the one drawn by Neroni. When I attempted to reconcile all these maps I was confronted with great differences in names and numbers of prefectures (fu) and townships (si), not to mention the smaller places. All this leads me to believe that these maps are based on indigenous drawings by different Chinese authors and that it will be difficult to say who among them is the best…”

06

Empires des Mongols Conrad Malte-Brun (1837)

Conrad Malte-Brun (1755-1826) was a Danish-French cartographer and revolutionary with a fervent dedication to the ideals of a free press. He played a key role in establishing several French cartographic organizations, including the Paris Societe de Geographie. Following in his father’s footsteps, his son, Victor Malte-Brun, continued his legacy by republishing his father’s works and creating maps of his own.

07

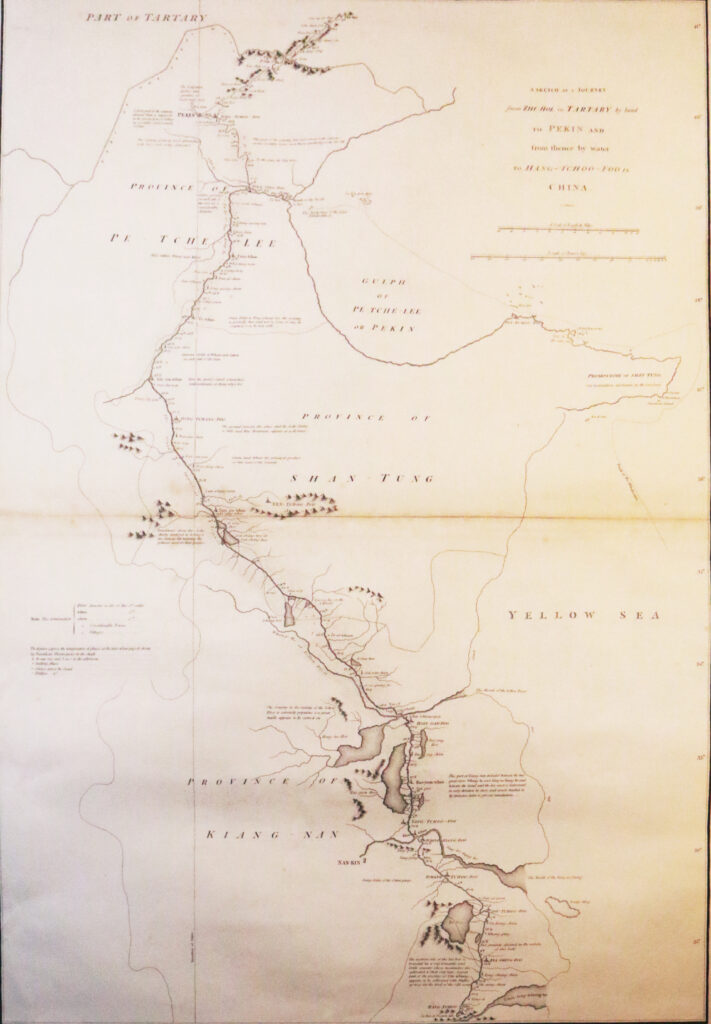

A Sketch of a Journey from She-Hol in Tartary by Land to Pekin and from Thence by water to Hang-Tchoo-Foo in China

The inaugural British embassy to China, famously known as the Macartney Embassy or the Macartney Mission, was led by George Macartney in 1793. The journey took Macartney from Zhe-Hol (Chengde) to Beijing, and then southward to Hang-Tchoo-Foo (Hangzhou) via the Great Canal of China. Despite being diplomatically unsuccessful with no political outcomes, Macartney’s expedition proved significant in mapping new geographies and customs previously unnoticed by Europeans.

This sketched map is credited to John Barrow (1764-1848), who accompanied Macartney on the journey and served as the comptroller of the mission. Barrow is most renowned for his role as the Second Secretary to the Admiralty from 1804 to 1845. Following the China expedition, he continued to accompany Macartney on later missions, including one in South Africa, and later in life became a dedicated advocate for Arctic expeditions.

George Nichol (1740?-1848) was a Scottish-born bookseller who served as the bookseller to King George III for over 40 years. Operating his printing press, he published accounts of government-funded expeditions, including James Cook’s exploration of the Pacific Ocean and the Macartney Chinese expedition. Benjamin Baker (1766-1841) held the position of Principal Engraver for the British Admiralty and the British Ordnance Society.